Vincent van Gogh

Life in Arles

On 20 February 1888, Vincent van Gogh arrived in Arles. Before that, he had lived in Paris for two years, where he had developed a thoroughly modern style of painting.

During the more than fourteen months which he spent in Arles, he created a multitude of paintings and drawings, many of which are nowadays seen as highlights of late 19th century art.

Tired of the busy city life and the cold northern climate, Van Gogh had headed South in search of warmer weather, and above all to find the bright light and colours of Provence so as to further modernize his new way of painting. According to his brother Theo, he went “first to Arles to get his bearings and then probably on to Marseille.”

That plan changed however: Van Gogh found in the beautiful countryside of Arles what he had been looking for, and never went to Marseille.

At first, the weather in the South was unseasonably cold, but after a few weeks Van Gogh was able to set out and discover subjects for his works. Vincent had a collection of Japanese prints, had read about Japan and become a great admirer. He had hoped to find the light, colours and harmony in the South that he knew from these prints. He did, and started to paint very Japanese paintings of blossoming trees and the Pont de Langlois. During the summer he drew and painted harvest scenes.

Painting the human figure had always been one of Van Gogh’s most important artistic goals, and he had a special love for peasant paintings. In Arles, he decided that he wanted to modernize this genre, by choosing the subject of the sower. He also painted portraits and still-lives, and confessed to Theo : “I am painting with the gusto of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse”.

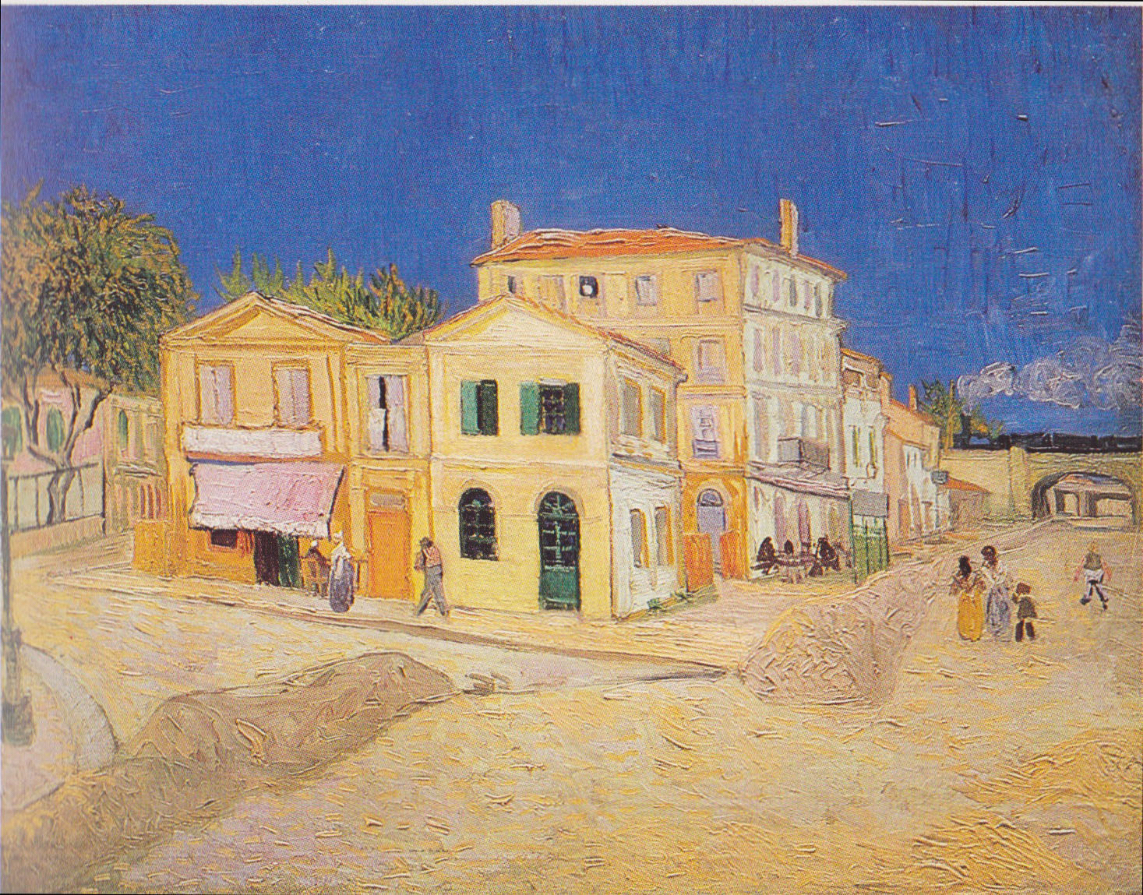

In May, Van Gogh rented the yellow house, in which he lived and set up his studio. He had hopes of establishing a collective studio in the South, were other painters would join him.

On 23 October, Paul Gauguin came to Arles. The two artists lived and painted together for two months. It was a time filled with great mutual inspiration, but in the end their characters and artistic temperaments clashed.

On 23 December, Van Gogh suffered a mental breakdown – probably a first sign of his illness – and cut off a part of his left ear. Gauguin left, and Van Gogh’s dream of a studio with other painters was shattered.

He spent some more time in the hospital after a second breakdown in February 1889. He continued to work in Arles for a few more months, but had himself interned voluntarily in the asylum in Saint-Rémy on 8 May 1889.

Arles cityscapes

During his career as an artist, Van Gogh lived in several cities – The Hague, Antwerp, Paris, Arles – and in all of them he found subjects for his work. Except for some drawings of Antwerp, he always showed a remarkable lack of interest in cities’ old monuments. Van Gogh sought his inspiration mainly in everyday life and relics from the past did not hold much interest for him.

Arles proved to be no different. With the exception of the sarcophagi of the Alyscamps and the courtyard of the hospital where he was treated after his breakdowns, no ancient monuments feature in Van Gogh’s work. He painted ordinary subjects such as a viaduct beneath the railway, and bridges, most notably the iron structure of the former Trinquetaille bridge. The banks of the river Rhône within the city found their way into his work, as did the Canal Roubine du Roi, just northeast of the town. Van Gogh had an unusual talent when it came to transforming such simple themes into original and captivating compositions.

He admired the serene qualities of parks and gardens, and painted both in Arles. The public garden next to the Roman Theatre greatly appealed to him and was the subject of four paintings, which he called “The Poet’s Garden”.

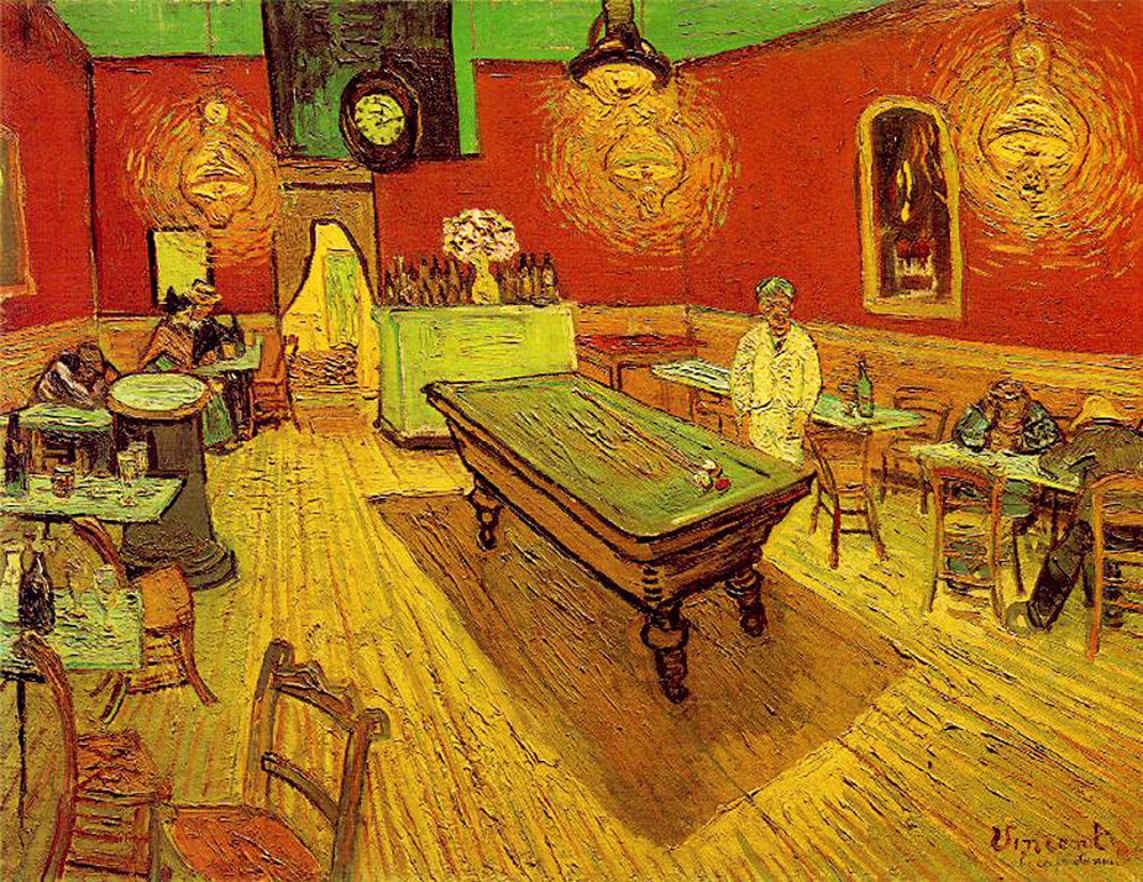

Several of his cityscapes became true icons in his oeuvre. The small house on Place Lamartine, in which he lived (no longer exists), is the central feature of the painting commonly known as “The Yellow House”, but which Van Gogh called The Street. A remarkable scene was painted at night: Van Gogh set up his easel near the Café de la Nuit on the Place du Forum and painted the café, bathing in yellow light, against a starry sky.

During Gauguin’s stay in Arles, the two artists made several paintings of the Alyscamps on the south eastern edge of the old town. All of them are very atmospheric autumn scenes, as is appropriate for this ancient necropolis.

During his second stay in the hospital of Arles, the 16th-17th century Hôtel-Dieu, Van Gogh made a painting and a drawing of its beautiful courtyard, recording his surroundings during this difficult stage of his life.

A view of Arles is included among many other paintings and drawings, such as “Field with Flowers near Arles”, in which irises in the foreground dominate the image. In these works, the town functions as a backdrop to the landscape.

Arles countryside

The topography of many of the landscape paintings and drawings, which Van Gogh made in the countryside of Arles, can no longer be established with any certainty. Since his time, much of the region where he worked has been further cultivated, while orchards and wheat fields have disappeared, as well as farmhouses and other elements of Van Gogh’s images. In several cases, however, where and what he painted is well known.

Located just over two kilometres to the south of Arles, the Pont de Réginelle (or Réginal), commonly known as the Pont de Langlois after the former bridge-keeper, was a particularly favourite subject for Van Gogh during March-May 1888. It features in several paintings and drawings. With its elegant shape and slender structure, the Pont de Langlois was eminently suitable for the harmonious Japanese atmosphere, which Van Gogh sought to express in his work. The bridge has since been destroyed, but then replaced by a similar construction.

The building of the medieval abbey of Montmajour took several centuries on a 43-metre high hill, five to six kilometres to the northeast of Arles. It was famous and even recommended to tourists in the Baedeker guide to the South of France as being out of the way, but worth the trip.

Van Gogh, who never minded a long walk, discovered it soon after his arrival. Although usually not enthused by ancient monuments, he was captivated by these ruins set in the middle of a large plain and surrounded by an impressive landscape.

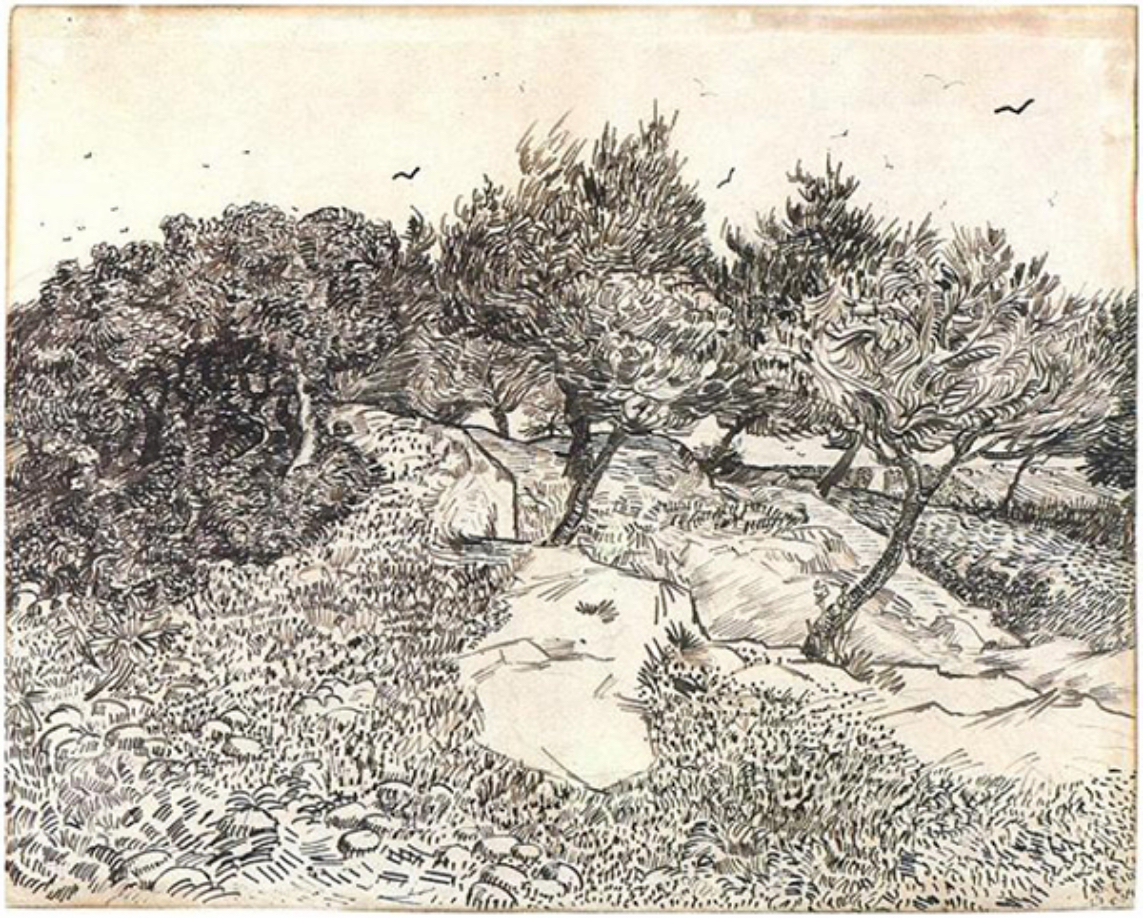

In the second week of May 1888, the abbey and its environs became the subject of a set of seven drawings, known as the “Montmajour series”. These middle-size drawings were followed by a second Montmajour series in July. On that occasion, Van Gogh worked on larger sheets and created six drawings, which are real highlights in his oeuvre.

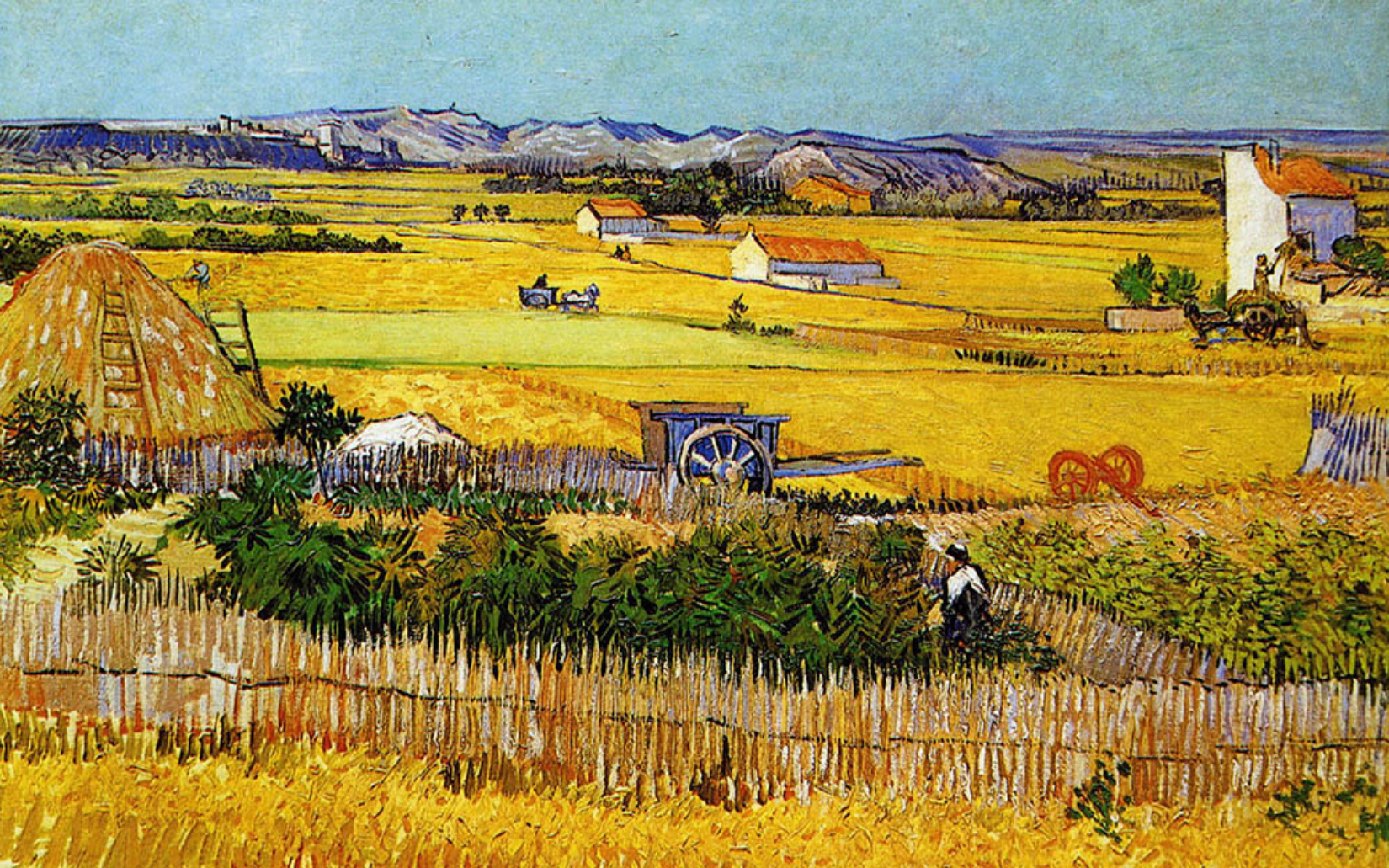

Montmajour overlooks the large plains of La Crau, which can be seen in two of these six drawings. La Crau also became a major inspiration for Van Gogh. In his famous “Harvest”, made as a painting and also three drawings, he depicted the harvesting of wheat, while adding a very visible blue cart as the focal point of the works. One of the last paintings he made around Arles was “La Crau with Peach Trees in Blossom”.

Light of the South

Before his move to Arles, Van Gogh had never been to the South. The warm and bright southern light and its effect on colour was one of the lures that made him leave Paris in February 1888.

Van Gogh was not alone in his search for light that had stronger qualities than the cool light of the North. Claude Monet had worked in Bordighera on the Italian Riviera in 1884, and would settle in Antibes for a while in 1888. Paul Cézanne lived and worked in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence. Adolphe Monticelli, who was greatly admired by Van Gogh, had lived in Marseille, while Paul Gauguin travelled to Martinique in 1887 to work in the light of the Tropics. Van Gogh would probably also have heard about the qualities of the light in the South of France from Paul Signac, who painted there, and from Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who was from Albi.

He had expected that the southern light and colour would resemble the atmosphere of his Japanese prints, and was extremely pleased when this proved to be true. To Emile Bernard he declared: “This part of the world seems to me as beautiful as Japan for the clearness of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects.”* Many of his letters from Arles pay tribute to the marvellous light and a newly discovered world of colour.

Van Gogh’s work from Arles is often associated with the colour yellow, which plays a prominent role in his works from that period. Van Gogh worshipped the Provençal yellow sun and its sulphur or gold coloured light. It flooded the landscape and enabled him to give his paintings the strong, unbroken colours that he had yearned for. The modern artist of the future, in Van Gogh’s view, would be a colorist as the world has never seen. The southern light was of prime importance for a modern palette, and he more than ever distanced himself from the grey palette of his Dutch years under a northern light.

Although his long days outside in the hot weather sometimes tired him, he felt the light and the heat improved people’s health and mood. The sun, which plays a key role in so many of his works from Arles, became almost a deity: “Ah, those who don’t believe in the sun down here are truly blasphemous.”**

Original French: * “Le pays me parait aussi beau que le Japon pour la limpidité de l’atmosphère et les effets de couleur gaie.”

** “Ah, ceux qui ne croient pas au soleil d’ici sont bien impies.”

Colours and brushstrokes

During his Dutch years, Van Gogh worked in dark tones and grey colours, applying his paint with a heavy, expressive brushstroke. He studied the theories of colour, as used by Eugène Delacroix and learned about contrasts, but with his sombre palette failed to make them work.

After his move to Paris in early 1886, he realized where he had gone wrong. With his new command of bright and strong colours, he was now able to work both in subtle contrasts (such as yellow and green), and with the strongest colour contrasts possible. That last one is a complementary contrast: red against green, blue against orange, or yellow against purple. At the same time, he experimented with the lively brushstroke of the impressionists, as well the different styles and techniques used by his avant-garde friends. He came to admire Adolphe Monticelli, who painted in strong colour contrasts with a heavy impasto. Japanese prints taught him how to work with large areas of bright colour.

Thus armed with a vast new array of possibilities, Van Gogh came to Arles to further develop his modern style. The bright light of Provence led him to even more daring colour adventures, with Delacroix as his guide. Complementary contrasts enabled him to make his colours even more expressive. The Sower of June 1888 was an ambitious attempt to make a modern figure piece by means of colour. Van Gogh used the complementary contrast of a purple field and a yellow sky, and then painted yellow lines around the field, and purple lines around the sky.

His use of red and green in The Night Café in September was quite exceptional. They dominate the painting, and Van Gogh explained: ‘I’ve tried to express the terrible human passions with the red and the green.’*

Amongst his fellow avant-garde artists, Van Gogh stands out because of his forceful impasto. Artists like Gauguin, Bernard and other painters working in Pont-Aven, worked with prominent areas of colour, too, but they preferred to use a subdued, flat brushstroke. Van Gogh’s work from Arles is the opposite. In most of his best works a prominent role is given to the handling of the paint. He sometimes used a more structured pattern of brushstrokes, such as in the background of his Still life with Sunflowers. In other works he applied the paint in a more spontaneous, lively yet always controlled manner. In all cases, colour and brushstroke merged together to create Van Gogh’s uniquely expressive style.

* Original French: “J’ai cherché à exprimer avec le rouge et le vert les terribles passions humaines.”

Drawings in Arles

Van Gogh is generally perceived as being one of the finest draughtsmen of the impressionist and post-impressionist era. While many of his earliest drawings were rather clumsy, he went back to work again and again so as to master this craft. For the first three years of his career, he worked mainly as a draughtsman. A good command of drawing was traditionally considered to be an essential basis for painting, and Van Gogh cherished that principle.

As a result, he became an excellent draughtsman long before his paintings started to show real promise. When he worked in Paris from early 1886 to early 1888, where he developed a very personal modern style, he concentrated on painting, not on drawing.

Van Gogh made drawings using various techniques, such as works in pencil, black chalk and other dark materials, as well as drawings in watercolour. His most outstanding talent, however, was with the pen. His virtuoso command of such a tool came to a head in Arles when he discovered a type of reed that he could cut and turn into a pen. This reed pen enabled him to make drawings with a remarkable range of lines, coils and dots, which are extremely lively, yet always controlled.

His first drawings in Arles date from March 1888. Japan was always on Van Gogh’s mind in that period, and these early drawings are the approximate size of the Japanese prints that he collected. The great draughtsmanship of Japanese artists was an example for him: ‘The Japanese draws quickly, very quickly, like a flash of lightning, because his nerves are finer, his feeling simpler.’* Van Gogh must have seen Japanese brush drawings while he was living in Paris, and some of his drawings stylistically resemble these works. He also made several watercolours with broad, flat areas of colour, which were inspired by Japanese woodblock prints.

Van Gogh produced several figure and portrait drawings, including a young Zouave and the postman Joseph Roulin. Landscapes, however, dominate by far. At Montmajour, overlooking the great plain of La Crau, he made two series of landscape drawings with his reed pen. The first one consists of smaller sheets, while for the second series he used large, whole sheets. The so-called second Montmajour series is an astonishing achievement, some drawings show a just how he had now mastered the Japanese technique, while others are even more refined. La Crau was also the location where Van Gogh studied harvesting, the subject of many paintings and drawings from the summer of 1888.

There is a strong relationship between Van Gogh’s drawings and his paintings. Sometimes a drawing acted as a model for a painting, at other times he would make drawings after paintings. Three series of “drawings after paintings” were sent to his friends John Russell and Emile Bernard, and to his brother Theo.

Musée des Beaux Arts de Tournai